|

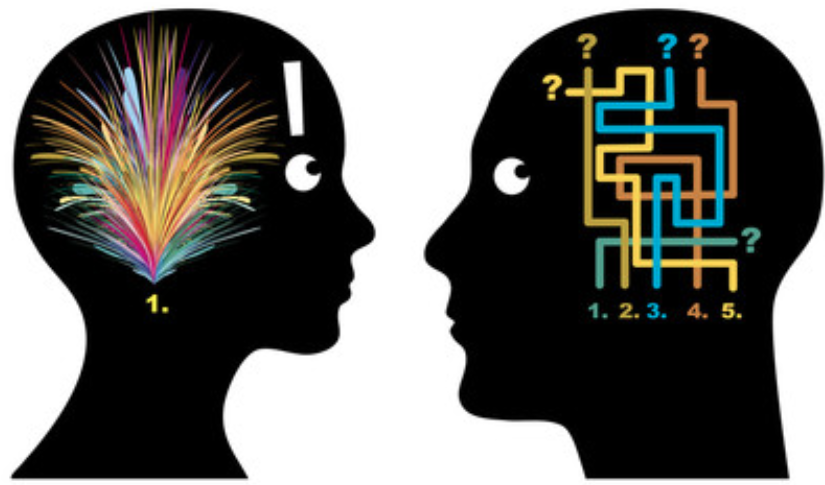

One of the layers in helping people with health and fitness is to help with critical thinking and sometimes formal logic. We all constantly make mistakes of equating opinions with arguments, induction with deduction, and then equating validity with soundness. Soon, everyone is talking past one another, including your own internal dialogue disagreeing inside your own head. That’s a lot of distinction to keep in mind. So for today, just consider validity and soundness.

Whether you are vexed at your own inability to listen to yourself or you’re frustrated that other people just won’t see things your way, you can experience some peace by discovering just where exactly the roads diverge. It could be that both sides are mistaking opinion (even expert opinion) for argument, induction for deduction, statistical trend for known mechanism, and validity for soundness. They are all distinct. But our minds tend to blur the lines. One day, perhaps I can turn this into my doctoral thesis on the psychology of wellness, in which I’ll detail every part. For now, let’s just consider validity and soundness. Consider first a valid but unsound deductive argument: 1.) Premises - Only people who eat too much dietary cholesterol will get heart disease. - You are a person who eats too much dietary cholesterol. Conclusion - therefore, you will get heart disease. The argument is valid, but unsound. What makes it valid is the construction. The construction is such that as long as the premises are true, the conclusion can’t be untrue. However, that isn’t soundness. An argument is sound only when its premises are true. Oftentimes, we begin with an untrue or at least contentious premise, and present a completely valid argument. People don’t accept the truth value of the conclusion, not because the argument is invalid or because they’re ignorant, stupid or evil, but because WE didn’t begin with an accepted premise. Consider now a sound, but invalid argument: 2.) Premises - All people with heart disease tend to have had elevated VLDL. - You have had elevated VLDL. Conclusion - therefore, you have heart disease. Sound; but invalid. Both premises are true. But the conclusion can be false. We only established that people with heart disease tended to once have had VLDL. We did not establish that all people who once had elevated VLDL have heart disease. In fact, this very common mistake is a logical fallacy with a name: affirming the consequent. We took the starting premise (if A, then B), affirmed the consequent (B) in order to conclude with the antecedent (A). Take a moment to reread this. You’ll likely find that the vast majority of super smart arguments are well-intentioned, well-informed, well-thought-out, but both unsound and invalid. That’s to say nothing of the common conflation of opinion with argument, induction with deduction, and statistical trend with known mechanism.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Elev8 Wellness

|

LIVE. AWESOME.We offer the highest quality in personal fitness, nutrition, and mindset coaching, helping you achieve your fitness, health, wellness and performance goals no matter the obstacle. With virtual online training and private, in-studio training we make it easier to reach your wellness goals safely.

No more can't. No more not good enough. If you compete in a sport, let your mind no longer hold you back from being the greatest. If you don't, let your mind no longer hold you back from being the best version of you that you can be. Sign-up for a Tour Covid Screen Waiver Elev8 Waiver Become an Elev8 Instructor Space Rental |

6244 lyndale ave. s., minneapolis, mn 55423

|

© 2021 Elev8 Wellness LLC. All Rights Reserved. site map | contribute | SITE BY Sproute Creative

RSS Feed

RSS Feed