|

“Feet at hip width, torso upright, chin up, knees behind toes,” they bark. It’s a well-intentioned set of cues... which work for exactly no one. That isn’t entirely fair. They work for a little less than 1 out of 10 people. That same 1 out of 10 then tell the rest of us how to squat, even though it is a physical impossibility for the other 9 out of 10.

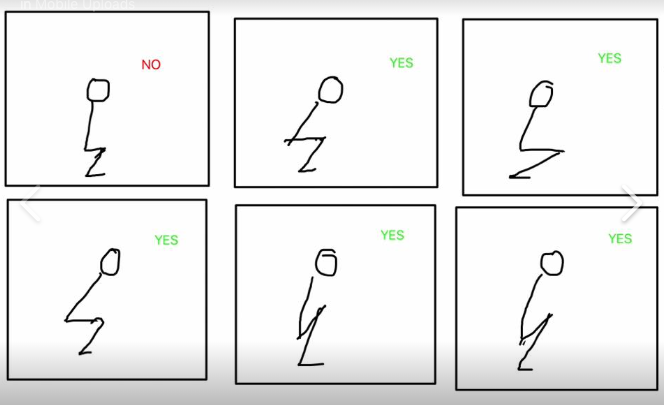

Anthropometry. If your coach doesn’t know this word and acutely understand variable level lengths, he’s missing the fundamental tool in how different athletes should move and train. There are many skeletons which cannot even approximate certain positions. I have a client who is 5 inches shorter than I am, but her ASIS (top front of hip bone) is 2 inches higher. I have a long torso. She has a short torso. There is no amount of effort which will make us look similar in a squat. A lot of coaches don’t know this. It isn’t an issue of muscle tightness, muscle insertion, fiber type, strength, injury history, or skill. Our skeletons CANNOT squat the same way. In fact, the look of a squat is almost entirely immaterial. There are much more important cues with feel, activation, bracing. These are far more important than what it “looks like.” That’s why Olympic lifting training facilities don’t even have mirrors. Your squat doesn’t need to look like anything. But it does need to feel like something. Anthropometry is a fascinating subject. It helps us explain why some athletes train far smarter and harder than others, only to lose to less dedicated opponents. It’s why people might call a waify 160lb male “built” if he has a 16 inch collarbone and then NOT call a heavily-muscled 240lb male “built” if he has a 10 inch collarbone. No amount of training can overcome certain skeletal ratios. Some levers define performance. Some levers create an illusion of impressive build. The levers won’t change. Every squat is going to look different. Every exercise is going to look different in different bodies. Mostly, people must assume a wider than hip stance, and bow much farther forward than they tend to think is prudent for a squat. But then there are a handful of sensory feedbacks which are universal: Feel glutes control your squat. They must contract powerfully. Feel knees push away from each other. Low lats and hamstrings must be engaged. Feet grab the floor. With breath held, going into the bottom of the squat will feel MORE stable and stronger. These bladders of air we call lungs help brace the torso and produce more force-producing tension. There is a lot of additional nuance here with ranges, ankle mechanics, spinal position change, etc. Directives around forward knee position are largely overblown. But again, a lot of that is “looks.” You can jut the knee forward and jam it into crazy ranges of motion if you stay aware of proper feel. We want to focus on feel. What I’ve discovered is that as people become increasingly skillful with replicating feel, they become more reliably athletic. That is, someone whose form looks good doesn’t necessarily have any lower risk of back injury, irritation, and aggravation. But someone whose form looks bad while they have proper activation, breathing, and sequencing, doesn’t get hurt. I have clients who’ve become so skilled with the feel that their risk of injury is almost nil. We could put 1000lbs on the bar. It’ll either move or it won’t. But they won’t they get hurt. People who haven’t studied anthropometry can’t make this claim, because they’re still stuck in a looks-dictated paradigm. I don’t care about the look. Do you feel the appropriate feedback? No. Then you’re unsafe no matter how good you look. Yes. Then you’re safe no matter how bad you look.

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Elev8 Wellness

|

LIVE. AWESOME.We offer the highest quality in personal fitness, nutrition, and mindset coaching, helping you achieve your fitness, health, wellness and performance goals no matter the obstacle. With virtual online training and private, in-studio training we make it easier to reach your wellness goals safely.

No more can't. No more not good enough. If you compete in a sport, let your mind no longer hold you back from being the greatest. If you don't, let your mind no longer hold you back from being the best version of you that you can be. Sign-up for a Tour Covid Screen Waiver Elev8 Waiver Become an Elev8 Instructor Space Rental |

6244 lyndale ave. s., minneapolis, mn 55423

|

© 2021 Elev8 Wellness LLC. All Rights Reserved. site map | contribute | SITE BY Sproute Creative

RSS Feed

RSS Feed