|

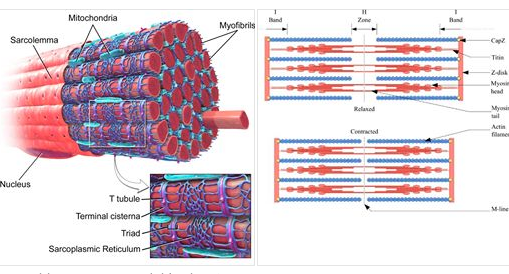

A long-held stretch doesn’t do what you think. In fact, it can’t. A sarcomere cannot be taken any farther than the end of the filament cross bridge without detaching and becoming non-functioning. This is biological fact.

Muscle cross-sections look a lot like bridge cables (see diagram 1). There are cables within cables. The outer cable is the myocyte or muscle fiber. The inner cables are myofobrils. The myofibrils are themselves overlapping layers of filaments which slide closer when a muscle contracts and farther when they relax. When the inner cable reaches the end of its elasticity, it will snap. That’s a fray. As enough inner cables snap, the whole outer cable will snap as well. You see, the filaments can only slide as far as there is some cross-connection (see diagram 2). Once they go past that, a collagen filler goes in its place. The filler doesn’t contract (since it is no longer skeletal muscle), and it further resists the modest amount of stretch which the previous but now destroyed myofibril had (reference Davis’s Law). The good news is that we all have signals from our nervous systems which attempt to prevent this sort of damage event. When the nervous system senses lengthening of those filaments, there is a natural phenomenon of protection to contract the muscle in order to prevent filament detachment. A long-held stretch “works” by wearing out this natural protection. Static stretch IS neural dysfunction. You are literally actively detraining the natural safety precautions in the body when you hold a stretch. And we know this. Research is conclusive that force production drops DRAMATICALLY after static stretches (https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/m/pubmed/17194246/). Speed drops. Power drops. There was a reason that you experienced pain or discomfort at the end of a stretch. That was the end of your current safe range of motion. Jamming on the tissue to force it farther makes about as much sense as poking an already-angry bear. When people experience the short-lived relief after stretching like this, it likely has more to do with endorphin release from experiencing trauma than any improvement in human performance. Though certain modalities of “stretch,” like proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation (PNF), seem more sophisticated, the outcomes are questionable likely due to the vast array of beliefs and skills among practitioners. In fact, it’s difficult to use the terminology “stretch” because of people’s expectations so aligning with the definition which aims to DEtrain proper nervous system governance. Thus, instead, the aim must be to mobilize. That is, we are really trying to improve control through greater ranges of motion. Rather than overcome natural safety systems in the body, we can work with them and develop them further. There’s no need to blunt them, dull them, tire them out. A good starting point is better understanding reciprocal inhibition. As one muscle shortens, the opposing side must lengthen. When you flex at the elbow, this isn’t purely a product of the biceps shortening, but also the triceps lengthening. That is a natural healthy neural relationship. And it exists throughout the body, though in slightly more complicated iterations. Keeping it simple, when you flex at the hip and extend at the knee (a kick), the hamstrings must lengthen to make this possible. Yes, there’s a little more to it than that with regard to all kinds of other muscles and structures. But just keeping it simple, imagine slowly raising ones knee and extending the foot out into a kick. In fact, slow controlled kicks like this are a staple of various martial arts. We aren’t trying to dull the nervous system’s protection mechanism. We are working with it. Slightly more complicated is a squat. Many different structures must work in concert, creating force couples, activating synergists, balancing, bracing, and so forth. Nonetheless, as one descends, there is control of lengthening in the knee and hip extensors. Over time, while listening to the nervous system feedback and working with it, one may squat more deeply (if desired) and at different angles with greater fluidity. Additionally, what people may interpret as “tightness” varies a lot. In most cases “tightness” is weakness. The body is assuming short positions because the tissue is too weak to be safe while lengthened. You are tight because you’re weak. Your nervous system is protecting you until you strengthen and make whichever affected tissue denser. Stretching weak tissue thinner and longer is precisely the opposite of your need in that case. Sometimes the back is “tight” because a night of sleep expands intervertebral discs (you’re taller after sleep), and that increase in their volume is pressure which reduces available range of motion. That should NOT be stretched out. Sometimes “tightness” is unregulated blood sugar (systemic inflammation). With insulin high, blood volume high, swelling high, how is tissue supposed to move easily? Various distortions, injuries and imbalances lead to other issues with muscle inactivity or firing sequence problems. There’s no way to stretch out any of those. All that said, gentle mobilizing, gradual activation, additional stability, and ultimately strengthening is always indicated, regardless of underlying pathology. Static stretch can ruin you. But proper mobilizing could save your life. photo credit: 1. Blausen.com staff (2014). "Medical gallery of Blausen Medical 2014". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.010. ISSN 2002-4436 2. Richfield, David (2014). "Medical gallery of David Richfield". WikiJournal of Medicine 1 (2). DOI:10.15347/wjm/2014.009. ISSN 2002-4436

0 Comments

Your comment will be posted after it is approved.

Leave a Reply. |

Elev8 Wellness

|

LIVE. AWESOME.We offer the highest quality in personal fitness, nutrition, and mindset coaching, helping you achieve your fitness, health, wellness and performance goals no matter the obstacle. With virtual online training and private, in-studio training we make it easier to reach your wellness goals safely.

No more can't. No more not good enough. If you compete in a sport, let your mind no longer hold you back from being the greatest. If you don't, let your mind no longer hold you back from being the best version of you that you can be. Sign-up for a Tour Covid Screen Waiver Elev8 Waiver Become an Elev8 Instructor Space Rental |

6244 lyndale ave. s., minneapolis, mn 55423

|

© 2021 Elev8 Wellness LLC. All Rights Reserved. site map | contribute | SITE BY Sproute Creative

RSS Feed

RSS Feed